I have repeatedly read advice that states, “Write about what excites you, what is fun and/or meaningful for you, or you won’t be able to keep at it.”

So.

I write fiction about individuals who struggle to accept who they truly are.

Why? Because they are me. Over the years, I have learned to accept myself and change what is not truly me.

Like many, I grew up in a dysfunctional family.

My dad was depressed, angry, and totally controlled us through fear. My mom told my sister and I, “Don’t argue with him or disagree because it only makes him worse.” My younger sister and I were constantly anxious and stressed. Diann developed asthma; I developed migraines.

I didn’t realize at the time that we not typical. This situation was the norm for us. Years later I learned differently.

At 60 years old I began writing fiction—fiction about growing up like us.

My first story is titled Learning to Fly. Its two main characters are parts of me—who I was at their ages, and who I wish I had been.

Reading was my coping mechanism. After years of therapy I turned to writing.

I restate that writing is one excellent way to deal with trauma. I will show you how I did it by including a chapter of Learning to Fly with each newsletter, and what it meant to me.

I hope some of you will recognize events, feelings, and/or triggers of your own. What speaks to you?

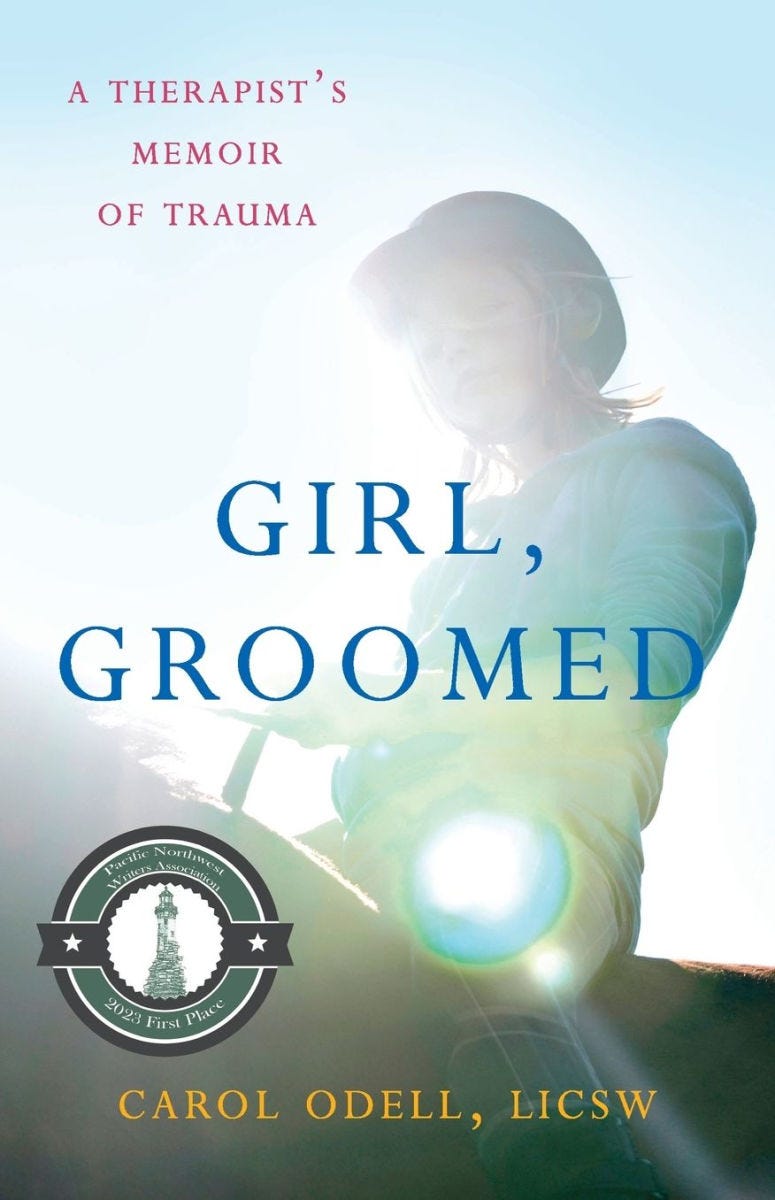

BOOK TALK

I recently read a supremely powerful book that spoke to me on nearly every page. Maybe it will speak to you.

“There is an innate fear that resides in all of us: the fear that we don’t belong, that we aren’t worthy as we are.”

Learning to Fly

Following is the first chapter of Learning to Fly with Niki and Kev. May we all learn to fly!

Chapter 1, Scene 1

Scientists Don’t Know Everything

I had just helped my best friend move into their new house on Rosemary Street, and Mrs. Monroy let him walk me home. Not that I need him to walk me home, but we like time together ... talking, planning, whatever.

Kev and I were born into military families. That’s Fate. No one has anything to say about the family they get stuck with. Deal with it, turb.

Kev’s dad’s an X2 Specter pilot. If you have to be military, that’s the best thing you can be. We’re going to be pilots. As good as his dad. Maybe better. We’ll see our home planet Gaia from space, even visit other planets, space stations, moon and asteroid colonies. There’s lots out there, more discoveries all the time. Being part of Allied Fleet takes education and hard work—and Fate on your side. Fate doesn’t like it if you ask for too much. Fate gives you nothing free. You have to work for it or ask in the correct way, the expected way, and discovering the expected way can be tricky. The expected way is a balance of showing you aren’t afraid, but not being too cocky either. Fate has you by the balls. Guys on Allied Fleet Base say that and I know what it means, even if people think I’m too young. If thirteen is old enough to go through a divorce, thirteen is old enough for anything.

We amble along the sidewalk through soft, summer twilight and chirps of those bright green tree frogs that perch on the end of your finger. Kev says he should have known the divorce was coming because of all the arguments, especially on nights before his dad left on another assignment.

Don’t parents realize? Do they think we’re deaf? I need to spit, but muzzle it.

Then he tells me his mom accused his dad of not wanting a family at all, or he wouldn’t keep leaving them.

Crimanolly.

“I might have done something,” he says. We keep walking, Kev’s hands in fists. Then he stops and regards his sneakers. “I mean, if I could’ve been more like he wanted. Better. I gave Mom trouble. She had to complain about me.” He crosses his arms over his chest. “I make her do things.” He kicks his sneakered toes at the sidewalk. “It was my fault.”

“You’re crazy. No way.” I shake my head.

“Well.”

Geez, There’s my dad, who I wish would get lost, the leech.

The street lamp shows glistening on Kev’s cheek. Right there on the sidewalk in front of someone’s neatly mowed lawn. I grab his arm and pull him to the shadow side of an elm next to the street. Trees are special, especially big old ones like this one. I push him back up against the bark and lean in with my arm around his chest. He doesn’t push back. It’s not a hug so much as us picking up tree energy. The bark is warm against my cheek. Kev says, like sand comes out with the words, “My mom drinks after he goes. She drinks a lot.”

Once my dad drank too much beer. Only once, yaz. He had a terrible headache after. Mom said he always got them when he drank, which is why he hardly ever did. Thank Gods, Yahweh, Jesus, Vishnu, Allah, Buddha, whatever. I can’t picture a woman like that, certainly not Mrs. Monroy. Freaky.

We stay under that elm while stars come out. I step back on one foot when it’s enough—I can tell—and Kev rubs his arm across his face and gives me a lopsided grin.

“Hey, Nik, hey,” he says. “I’ll survive. Thanks.”

“Thank the tree.”

He mimics Herbie on “Olden Days”: “Both a ya’s.”

He does, too, survive is what you’d call it. Like a big old caterpillar wound tight inside his cocoon. Until that storm at the lake.

* * *

Restitution Island on Lake Mirage. Our island. Magic. Nothing bad can ever happen here. Kev’s Granda Eli and Grana Rose have owned a cabin on the lake forever, and I am accepted as part of the family the first time I walk up the porch steps behind Kev when we were five. Granda tells stories, takes us hiking and fishing, and Grana Rose cooks fabulous food from her garden and bandages us when we hook one another instead of fish, or fall in the gravel drive and bloody our elbows and knees. The cabin is built of logs from trees nearby; pines and firs hug the beach fifteen feet from shore. Kev and I sleep on top bunks behind the stone fireplace. The wall between where we sleep and the front room stops short of the ceiling, and as long as we stay awake we can watch his folks, Grana Rose, and Granda Eli play cards.

I dream about the island. Ever since Granda takes us there in his boat, Miss Sunshine, when we were seven.

“This is a special place,” he says. He wakes us in the dark so Miss Sunshine can slide up onto the beach with the morning sun lighting the trees as he cuts the motor. We jump out to lapping blue water, sparkling white grains and tiny, scrabbling red crabs.

“This is how you tie a boat off, so she’ll be here when you return.” Our first lesson.

“Now, you see these marks in the sand? What do you suppose they are?”

That’s easy—we saw the crabs. We follow to see how they bury themselves in the sand and make bubbles and leave little tracks behind. Second lesson.

After exploring the beach, we wander under trees and peer under leaves and sticks and logs. The first day we forgot to have lunch. All morning we sampled leaves and roots and even bugs, daring who will go first. We learn what is poisonous, as well as what is safe.

We never tire of the island and go there as often as we can get Granda to take us. I ask him why we see no one else out there, as other families live around Lake Mirage.

“Because I bought the island years ago,” he says. “Folks around here know.”

The way he says it, you know not to ask more.

It is almost the end of that crummy summer of the divorce. Granda Eli plans to take us exploring, including Kev’s little brother, Tucker. Surely Kev will come out of his frozen state for this.

Tall, large-boned, lanky Granda ducks through the screen door and says it isn’t a proper day for a trip to the island because a storm is coming in from the southeast.

No island today. And Tucker is mopey as Kev.

Kev and Tucker follow me outside to watch the storm build, and Kev and I sit on a log at the campfire circle. Looks like a big storm, all right—the light is like inside a topaz bottle, and the horizon on the far side of the lake melts into a smear of bruised darkness. Thunder rolls, I hug myself, shiver in the cool wind, and want to jump up, run, dance in circles and scream at the sky. But here is Kev sitting next to me, all mopey, pushing the end of a twig around in the gray ashes of the dead campfire.

I squint through the blowing wind toward Miss Sunshine, covered in green tarp and secured with rope fore and aft at the end of the dock, bumping and rubbing against the used tires Eli nailed there years ago. She pulls at the lines like a wild sea creature. The yellow boat is a baby whale captured by the local fishers, trying to break free and return to her family that roams the wide ocean ... she could get loose with the help of ... the green-eyed daughter of the village’s best fisher, who understands her need to be free - - -

Scratch, scratch.

“That stick’s more interesting than the storm, huh?”

A flat, “I guess.”

I curl into my knees and watch the twig make serpentine traces in the ash. Icy wind blows hair into my eyes and shrills the pines. Low, gray sky rumbles. A loud crack makes me jump; its echo thuds in my chest. Shredded leaves swirl by. A saffron butterfly floats in at our feet, scoots across the ashes. The twig halts, and the butterfly settles next to its tip. A tracery of tiny veins splays a miniature delta across one torn wing. I hold my breath. Breeze scoots the butterfly, stops … scoots; a gust sends it flying. Two fat water drops plop craters into the ashes and puffs soft clouds. An icy drop slaps the back of my neck, making me look up.

“Hey, where’s Tucker?”

Kev lifts his head, glances around, leaps up. Yells, “Tucker?”

I turn toward danger—the water—where Tucker perches on the prow of rocking Miss Sunshine. Kev springs from the log; we watch open-mouthed as Tucker rises to his feet and waves…and the boat jerks loose from a mooring and flips him into the freezing whitecaps.

Kev takes off like a specter out of a launch tube with me right behind. I reach the beach, sand clutching at my feet as in a slow motion dream. Kev tears across the sand ahead of me and dives into the waves. I hit water that freezes breath and mind—stroke, gasp, blink, grasp an arm, turn and splash foam and kick and get out of the biting wet until we are sputtering and coughing, crawling across the cloying sand, trying to catch our breaths.

“Geez, Tuck,” heaves Kev. “What’s the matter with you?” He yells, all dripping and spitting. “You know better!”

Tucker squeezes his legs against his chest, head down, teeth chattering. “You don’t want me around. I’m just in the way.” He peers up at Kev through wet lashes and hair. “I don’t want you to go away like Dad.”

Kev stares back with his mouth parted, blinks twice. “Tuck ... cripe, Tuck.” Kev rubs his hands on his thighs. He looks down and digs his hands into the sand, raises fists that squeeze wet sandy globs from between his fingers, then back at Tucker. “You and Mom are more important to me than anything. You and Nik. I won’t ... do like Dad … promise.” He pulls Tucker in, buries his face in his neck and hangs on. He grabs me in there, too, and we all rock together. We are soaked and boney and I am off balance leaning on my toes but, scram, this feels good.

Tucker wiggles, “I’m smothering in here.”

Granda calls from the cabin, and we run for it, not least because it will be warm and dry and we have to tell him about Miss Sunshine bouncing out there on one tether.

Tucker is at our heels forever after, but Kev doesn’t complain, so I don’t. Kev teaches Tuck how to throw a ball straight and catch a furry, big-eyed seelix without harming it. Helps him with homework, too. Kev even laughs again.

That winter, I write in my notebook: If a person stops thinking about themselves so much and cares for someone else instead, they get better right along with them. This idea doesn’t work with what we are learning about evolution—all that survival of the fittest stuff. But scientists don’t know everything.

Is anything in this chapter familiar to you? I would love to hear your reaction, either in comments or on our Chat.